The

“new wave” of Chinese science fiction can be traced to the writers who grew up during—or in some way experienced—the cultural revolution, with its grand utopian images of modernity in a socialist, classless state of permanent revolution. Rather than embracing the new Chinese society after the opening and reform era, they came to see the current obsession of economic growth as a

reinterpretation of past visions, once again trying to accelerate the historical process without thinking about its consequences.

For the influential Chinese writers in this article, continuation of unchallenged market capitalism is yet another doomed to fail utopian project which might lead to a dog-eat-dog society. This criticism is inherited in

younger science fiction writers, who see a changing China in its age of triumph, but also a society moving towards a dark path of selfish immorality.

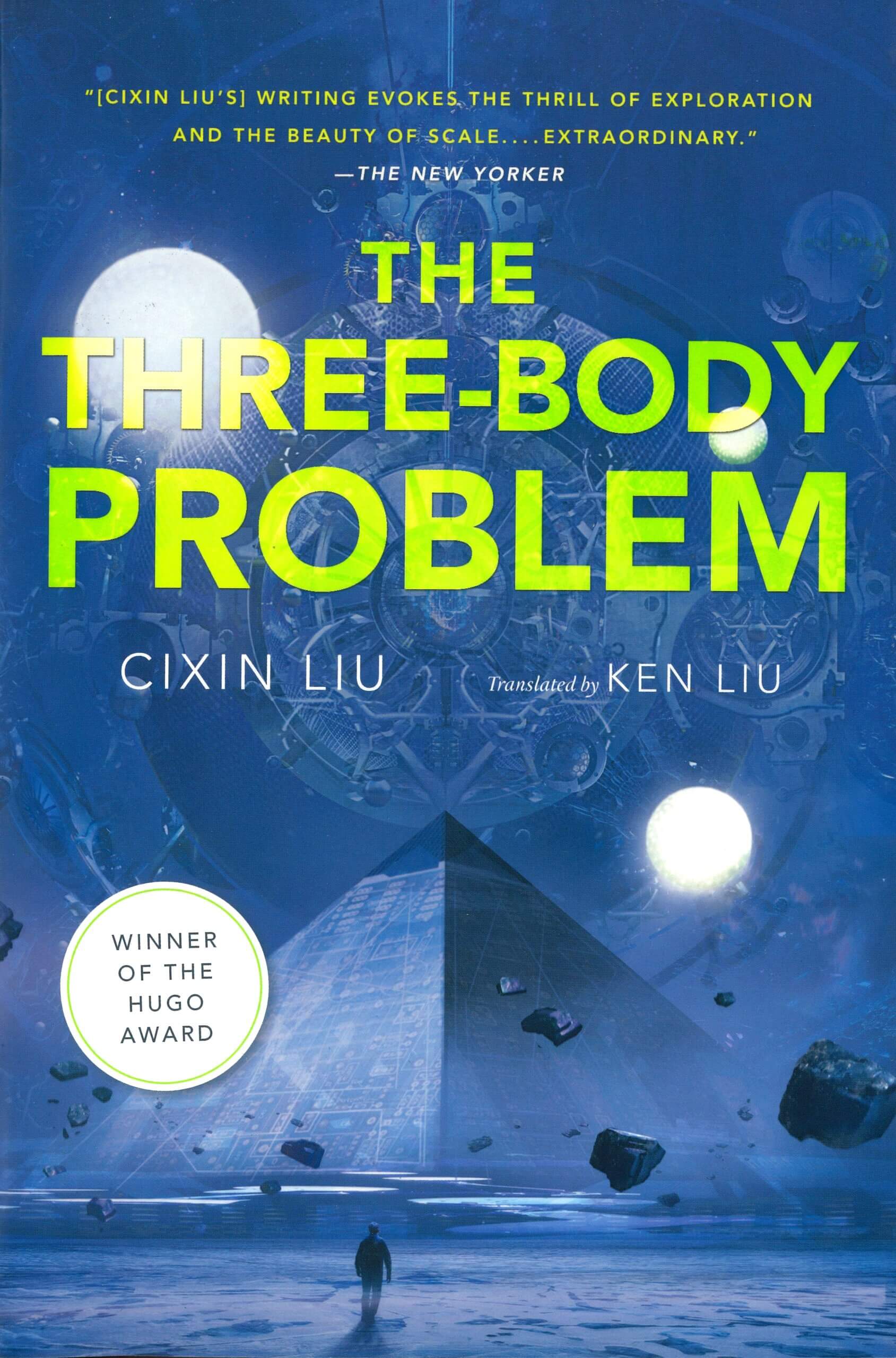

Now with all the technobabble out of the way, let us look at “the big three” of Chinese contemporary science fiction: Liu Cixin, Han Song, and Wang Jinkang. The previously mentioned Liu Cixin is by far the most celebrated and has become the new face of what is traditionally called

“hard” science fiction. Hard science fiction emphasizes technological accuracy and conveys a more naturalistic approach, which means that reality is explained according to some logical rules, and the story explores its implication in the “real” world. His magnum opus, the

Three-Body trilogy, builds up an epic, technology-driven world which slowly realizes its own insignificance in an ever-increasingly threatening universe. In such a world, humanity must ask itself: Where do we draw our moral lines when it comes to survival? This is a central theme in many of

Liu’s works. Humanity’s existence is accidental and unpredictable, while the laws of physics are constant. The universe is completely indifferent to our goals, morals, values, feelings, and our desire to create meaning out of it.

Cixin might be the man who put Chinese science fiction on the world stage, but Han Song and Wang Jinkang are equally influential back in their home country. They take more social or “soft” approaches, and tend to look at the dehumanizing effects of China’s rapid development.

Perverse images of gluttony, human degeneration, and greed are explored within societies obsessed with efficiency, speed, and personal wealth. Han Song is most famous for his

Subway series. In the first book, an unstoppable subway train travels around Beijing for eternity, with its passengers evolving into

monstrous creatures without any self-constraints. In his newer work the

Hospital Trilogy, we meet a self-learning algorithm controlling a hospital out at sea that is trying to end pain and suffering with the creation of eternal life. Instead of achieving this impressive feat, the hospital creates mindless patients being directed to die at the algorithm’s will. In Wang Jinkang’s

Ant Life, we encounter a scientist who has managed to extract a serum of selflessness from nature’s own model communist creatures: ants. From this, he eventually starts to create utopian communities with human subjects. Much like in the hospital, the dream turns into a nightmare when individual lives must be sacrificed for collective development.

The people behind the Chinese science fiction phenomena, from left to right: Liu Cixin, Ken Liu and Han Song.