17 May 2016.

The corpse of a young girl is found in a public toilet in the proximity of Gangnam station, stabbed to death by, supposedly, a stranger. A few days later, Kim Sunmin

testified as the perpetrator of the crime, admitting he had never met the victim before the fateful night and revealing the murder was due to his frustration of not being able to date a woman, arguably establishing the murder as an incidence of gender-based violence. This stance was not, however, shared by Seoul’s High Court, which

dismissed the case as a motiveless crime by appealing to Kim Sunmin’s mental health issues.

The Korean feminist association Megalia, which until the murder had only operated through its online forum, encouraged users and supporters to

gather in front of Gangnam subway station as a sign of protest and respect for the murdered woman, denouncing the rampant misogyny and the lack of gender rights they perceived in South Korean society. The mobilisation, however, riled the users of the antagonistic Ilbe Storehouse community (a male-exclusive, far-right online forum with gendered hate-speech), which led to

offline discussions between the two parties in front of the station, officially marking the start of the so-called “Gender Wars” in South Korea.

The described events consequently

initiated a rip-roaring wave of feminism in South Korea. In consequence, public awareness of the hardships Korean women have to face in a country that registers, for instance,

high rates of femicide and domestic abuse, as well as the largest wage gap in all OECD countries (amounting to

32.5% in 2019) increased. These feminist developments, however, have been demeaned by a horde of angry internet users who counter with chauvinist discourses on online forums and social networks, and endorse the contention which sees men as the

real victims of the Korean sexist society. In other words,

Gender Wars are nothing more than a social phenomenon resulting from a widespread sense of male frustration and disorientation brought on by the alteration of traditional society and its expectation.

Amongst these myriad sparks behind the fire of the gender wars in South Korea, the flammable tinder— that is, the economic and social background affecting the lives of Korean youths—demands inspection. This war-inducing context can be epitomized through

헬조선 Hell Joseon, a concept that emerged from the depths of the Korean Internet commonly used to

describe the country and its oppressive society.

On the edge of the Asian landmass, surrounded by enemy waters once sailed by fearsome invaders and confining with the sinister reign of the Kim dynasty; there is a wicked land that extends below the 38th North Parallel—commonly known as South Korea. Satirically referred to as 헬조선 or ‘Hell Joseon’ by its youngest inhabitants, this land is the native soil of a new generation of ill-fated subjects, doomed to be born and raised in a fiercely competitive society, where failure, offbeat life paths, and social mobility are in no way contemplated.

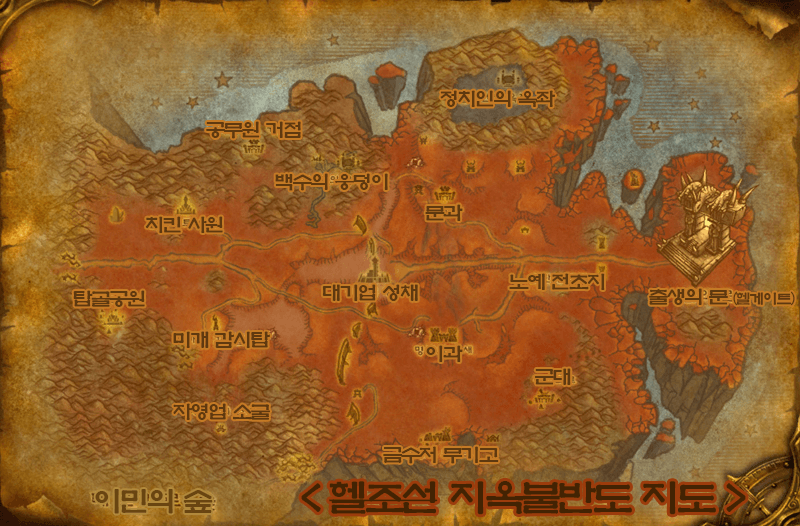

Describing such an infernal place is no easy feat. However, the symbolic illustration provided by

@Yazawa_Miho_ on Twitter may ease the process.

헬조선 지옥불반도 지도 “ The map of Hell Joseon, the infernal peninsula”

Source:

@Yazawa_Miho_ on Twitter

According to the map, which must be read from right to left, the woeful journey of Korean subjects starts at 출생의문,

the Birth Gate, which enslaves this hapless generation into a highly regulated system that dictates every aspect of their lives. Subjects are first subjected to an onerous education system – 노예 전조지

the Slave Outpost – in preparation of the

suneung exam that determines their academic and working future; and later to 군대

the Military, for which all able-bodied adult male citizens between 18 and 35 years old must serve for at least 21 months. After subsequently completing university education – either in 문과

Humanities and Social Science or in 이 과

Science and Engineering, the ultimate goal for the young denizens is to serve the mighty 대기업 성채

Large Corporations, which rule over Hell Joseon from the heart of the peninsula. However, due to an increasing level of youth unemployment rate—currently around

11.2%—Korean youth are forced to reroute towards 공무원거점

the Fortress of Bureaucracy or the 자영업소굴

the Lair of Self-employment, in order to escape the 백수의웅덩이

the Pool of Joblessness.

Hell Joseon is therefore depicted as a land of oppression and social constraints, in which the youth feel betrayed by a society that first nourished and then broke the promise of employment in big corporations.

Despite Hell Joseon’s brutal rules equally affecting men and women, the peculiar dynamics of Korean gender wars reveal that

part of the problem must be researched in deepening male social dissatisfaction. In the recent years, masculinity has indeed undergone a transformation which resulted in

the change of men’s role in society, sometimes actively—from

knight in shining armour to weary soldier that cries, “discrimination!”; other times passively—from

economic hero to job-market competitor; from unfailing

prince charming to partner that needs to be liked and chosen.

As illustrated on the map, embarking on military service is the earliest stage which marks the first conflict with the traditional gender role that young Korean men have to face. In Hell Joseon, male young adults are indeed expected to serve as

knights in shining armour under the modern conscription system. The legitimacy of such a system is secured by the principle of equality, for which all young men should equally serve in the military. A principle which, however, often

excludes those belonging to the upper classes, since they can easily evade service or get assigned to less-challenging duties thanks to their financial means.

Such abuse of power generated a diffuse feeling of injustice among young men, who commonly perceive the military service as a waste of time and worth avoidance, given the variety of negative impacts on their economic and social lives it has. Korean young men are thus refusing the traditional role of brave soldier proud to serve the nation, pointing the finger at inequality and, for the very first time, at gender discriminition. In this respect, the

report published by the Korean Women’s Development Institute exposed increasing ‘hostile sexism’ and ‘anti-feminist’ sentiments among Korean men in their 20s and 30s, who “tend to agree more with the statement that the current military system is discriminatory and women should also participate in the service”.

Another male role challenged by Hell Joseon’s society is the one of

economic hero: governments and corporations, heedless of labour market instability, have indeed implemented neoliberal policies which have caused the alteration of traditional male roles, making it arduous for young men to fulfil the role of breadwinner as prescribed by traditional society. However, instead of railing against neoliberalism,

Korean men direct their anger toward women, whom they perceive to be stealing their jobs. In a world in which the ultimate goal is to get hired by a large corporation—and in which such a goal becomes more and more unattainable due to

low employment rates—women are in fact now seen as rivals in the job quest, considering the gradual rise of women’s rights in society and the labour market, in no small part due to the recent

government policies aimed to expand female representation in the government and encourage the hiring of women in the private sector. Such a situation leads some male youths to believe that the status of Korean women

is even higher than that of men, thereby ‘justifying’ the widespread sexism and anti-feminist sentiments by appealing to

reverse sexism.

In precarious Hell Joseon,

prince charming is likewise a victim of (social) underemployment. It is no mystery, in fact, that Korea is currently facing a severe demographic crisis which is raising concerns about the ageing population, shrinking workforce and low birth rates. In 2018 it was indeed reported that fertility rate had fallen to a record low,

dropping below 1, or less than one baby per woman, for the very first time.

On the one hand, uncertainties raised by the country’s worsened economic situation might

discourage young couples from having children. On the other hand, one cannot rule out that marriage has lost its traditional appeal among young Korean women, who tend to either

avoid or postpone marriage and childbirth due to a newly gained economic independence and improved social conditions, derived from educational expansion and the changing occupational structures. Faced with this state of affairs, young men are giving voice to their social dissatisfaction resulting from the

insidious fear of failing in forming a family.

Alarming data and government reports are only part of the problem: as reflected by the gender clashes taking place in online forums and social media, such fear is mainly fomented by

inferiority complexes resulting from the difficulty in keeping up with the changing society. The new generation of young women is indeed far from the Confucian ideal of submission and condescension, and those who take part in the online debate

rebel against their expected role as objects of the male gaze, expressing their female identity by raising women’s issues and challenging male-dominated opinions.

As advocates and supporters of gender equality, these women commonly identify themselves as “feminists”. However, due to the

controversial activism exercised by radical groups like Megalia and Womad,

Korean young men have a bad opinion of the feminist movement, with which they maintain a quarrelous and aggressive approach during confrontations.

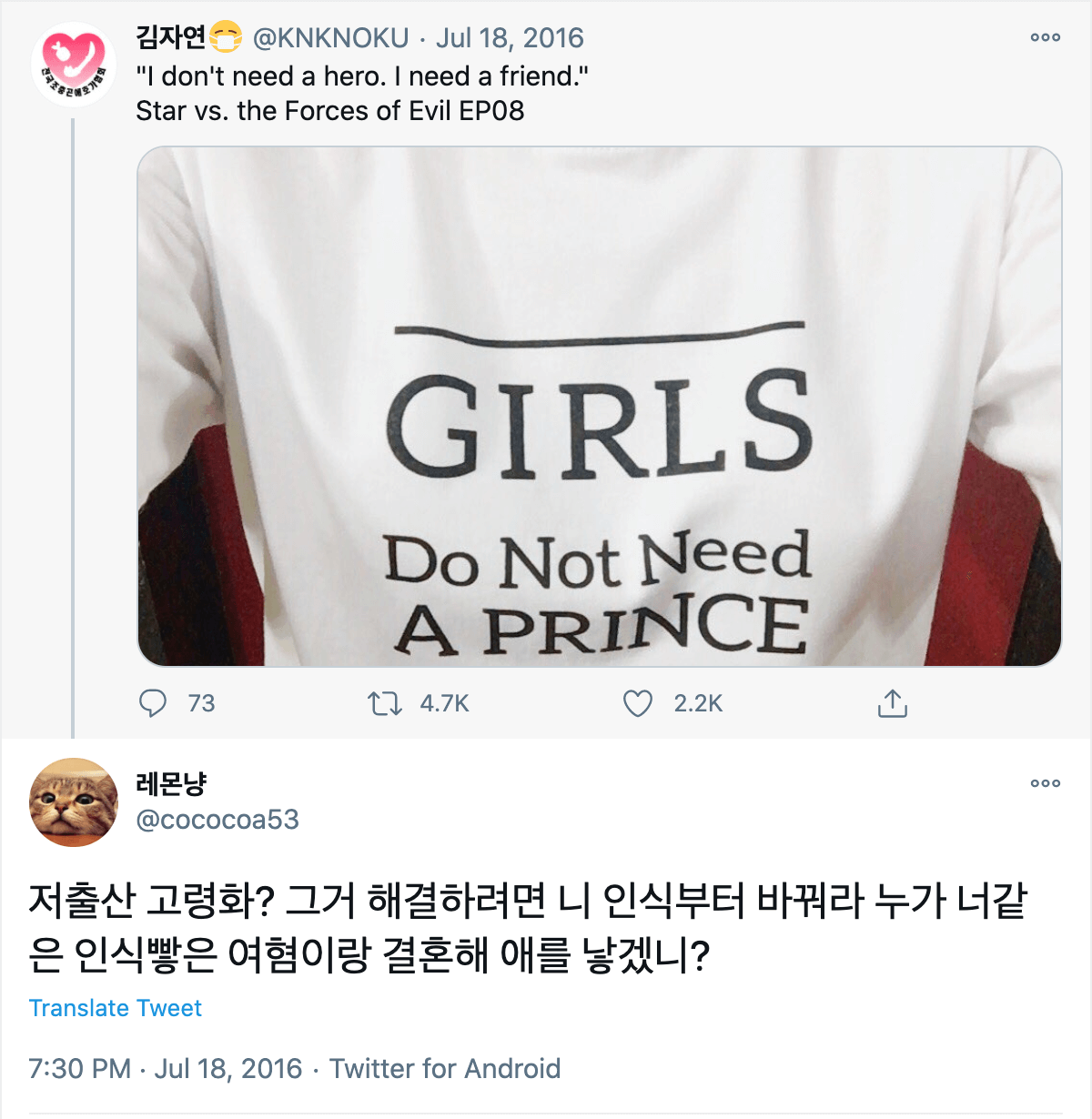

Feminists are indeed seen as a villain to defeat in order to re-establish social order and regain possession of their traditional roles.In this context, the actress Kim Jayeon bore the consequences of such conflict. Known to be a dubber in the ‘Closers’ video game, she accidentally caused an online revolt once she posted on her Twitter account a

photo of herself wearing a feminist t-shirt with the Megalian slogan “GIRLS do not need A PRINCE”. Both the videogame’s company Nexon and the actress’ account got inundated with complaints from Closers’ online community, indignant about the connection between Kim and the radical feminist organization. Such mass backlash eventually led the company to

fire the actress in order to comply with the customers’ ethics and sensitivity.

Leaving aside the injustice suffered, interesting is the analysis of the comments followed by the posting of the photo. Scrolling down the

Twitter thread, one can read multiple comments accusing Kim Jayeon of contributing to the decline of Korean society due to her feminist activism. In this regard, particularly emblematic is the tweet by the user

@cococoa53, which perfectly summarizes the frustration lamented by these failed princes charming: