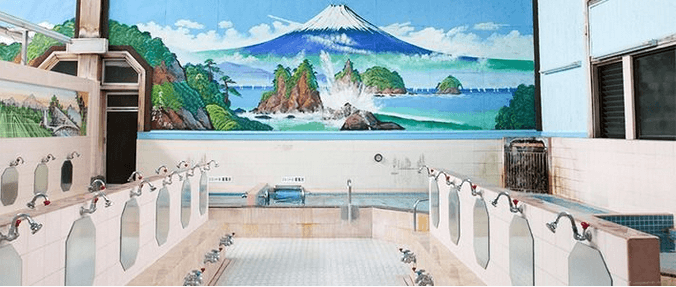

People are shedding both their clothes and their daily fatigue at the entrance, relaxing in the huge baths inside. The bath is over 50cm deep, filled with steaming 42 ℃ water. Nakedness somehow leads people to be honest, open-minded, and have mutual respect as human beings. They enjoy having casual conversations with others while admiring beautiful scenery through a window or in a wall painting … This is a typical scene in a public bathhouse, called

sento, in Japan. Such venues, however, have become rare in recent decades. In the 1960s, there were 2500 sento in Tokyo, but by 2020, the number dwindled to less than 500. There are multiple causes for the decline, such as the shortage of successors to run sento, the prevalence of private showers and baths at home, and the deterioration of sento buildings. On the other hand, there are hopeful signs for the industry, led by an uptick in sento popularity nowadays among a new generation of young devotees.

Sento has a long history of development in Japanese society. The earliest sento was attached to Buddhist temples in the 8th century and were open to people from a wide range of social statuses. They especially flourished during

the Edo period and functioned as a place where people can practice a hygienic life and socialize with others while getting away from the severe hierarchical relationships that dominated the era. Starting in the early 20th century, sento became more spacious bathtubs made of tiles instead of wood. Wood is still used today in the more traditional style of sento.

The sento is historically rooted in people’s bathing habits and the creation of social communities. As it is regarded as a public facility to maintain people’s well-being, they receive a subsidy from the government as well as a fixed fee for use. In recent decades, as the number of traditional sento has declined, a new style of sento, called “super sento” has spread throughout Japan. Super sento is a larger facility equipped with various kinds of baths and saunas, restaurants, and a huge parking lot, where people can spend longer periods with their family members or friends. Meanwhile, since it is run by a private company, it often faces intense competition with other super sento and withdraws from its business.

Despite these challenges, younger generations are increasingly reassessing the value of sento culture in contemporary social contexts. Sento started to regain public attention as a place to generate

social capital in an increasingly online world. Social capital is the accumulation of useful social relationships and networks. With accelerating urbanization and an aging population, it is becoming harder to sustain local community bonds and guard against social isolation. In this context, sento, gathered local people and created social bonds in the Edo period, is expected to reunite people living in urban areas and promote their mutual interactions and networks, which is significant value in the aging society.

The health benefits of sento are being reevaluated as well.

Scientific research has revealed that going to sento improves blood flow, balances the autonomic nerves, strengthens the immune system, and eases mental stress. Moreover, from around the 2010s, more young people have rediscovered old cultural attractions influenced by the “

retro boom”, the revival of interest in old-fashioned things, and the popularity of a famous comic book called “Thermae Romae”,

Young sento owners and some organizations have been taking steps toward the revival of sento culture. “It’s becoming increasingly difficult to survive just as bathhouses alone,” says

Kuryu Haruka, who works to preserve old bathhouses. Thus, they are adding new elements such as bars and events space to the conventional sento.

Minato Sanjiro, who is a new owner of Ume-yu, a historic sento in Kyoto, succeeded in increasing visitors by hosting concerts and flea markets at the sento and by advertising it online. Inari-yu is creating a community space in an adjacent building, where visitors can hang out and enjoy communal meals and exhibitions. A non-profit organization called

Sento & Neighborhood, founded in 2020 seeks to highlight the social and cultural importance of sento and ensure its preservation in the future. They are working with sento owners to plan repair, maintenance, and renovations of sento as well as researching its historical and social value. In 2019, this revival trend eventually led to the consequence that the number of sento visitors in Tokyo grew for the first time in more than a decade.

However, attacked by the covid pandemic afterward, sento faced a severe decline of visitors. In response to the crisis, some remarkable projects to sustain sento were held by young owners and companies.

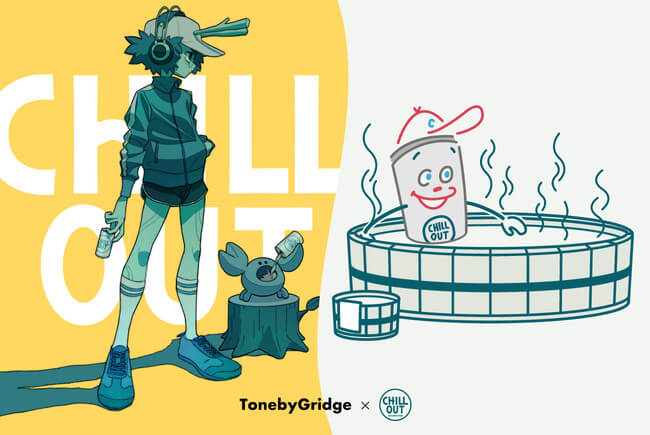

Kogane-yu, whose visitors plummeted by half during the pandemic, set up crowdfunding and got public support to carry out the large-scale renovations on their facilities. The renovation involved young designers and creators to devise a “brand-new” sento that attracts a wider range of generations and foreign people and was successfully completed in 2020. Startup companies

Endian and Gridge worked together to take up the project called “Mokuyoku Neo Chill experience project”. Since official covid measures encouraged “Mokuyoku (黙浴)”, that is, visitors not to talk with others while enjoying sento, this project aims to enrich the Mokuyoku experience by playing chill music radio produced by Gridge in the bathroom and giving visitors a relaxing drink, Chill Out, from Edian. The project was implemented at Kairyo-yu in 2021 and succeeded in drawing public attention.

For Japanese people, taking a bath in sento means not just cleaning their bodies but something more essential: the preservation of culture, maintenance of the local community, and pursuit of a healthier and happier life. To counter the phenomenon of disappearing sento, people in the younger generations rediscovered its value and utility to address issues in modern society and add more value to it for future preservation. Sento, a significant part of Japanese culture, is evolving while retaining its value for people’s well-being.