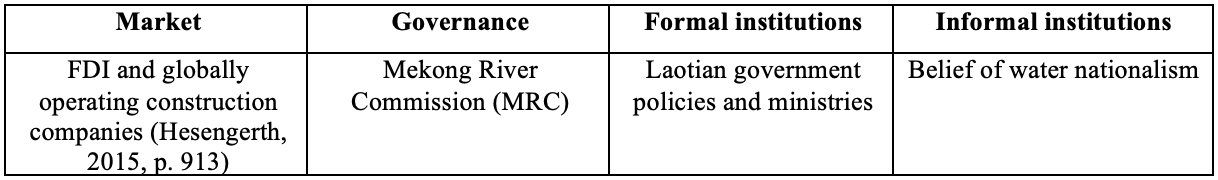

The state-owned electricity enterprise Electricité du Laos (responsible for electricity transmission and distribution, and energy exports) separated from the company EdL-Gen – Laos’ first publicly-held enterprise (Ministry of Energy and Mines, 2012, p. 21). EdL-Gen is responsible for power generation. Also, the Department of Energy was reorganized and diversified. The result is an improved bureaucratic infrastructure that facilitates government policies directed towards private investors since public resources to fund the hydroenergy sector are too limited, and hydroenergy policies are being increasingly oriented to the regional market instead of only following domestic demand (Chattranond, 2018, p. 123). At the informal level, the dam changed the perception of governments in the LM region towards believing that large-scale hydroenergy developments in the Mekong lead to improved preconditions for economic development (Grumbine, 2012, p. 94). This has led to a change in economic and political values towards more water nationalism, “the belief in the state’s ability to control and confirm national sovereignty over water“ (Chattranond, 2018, p. 25). Dams have become a source of national pride, depicted in the national emblem of Laos, videos of the national anthem, banknotes, and a frequent destination of foreign state visits (ibid. p. 114).

Heritage vs. Hydroenergy

Dams are a vital factor in Laos’s economic development because they enhance the country’s national creditworthiness by functioning as collateral. Furthermore, they diversify and intensify regional relations, and they increase the willingness of private financiers to provide capital (Grumbine et al., 2012, p. 94). However, since the hydroenergy sector is so heavily dependent on foreign investments, the commitment of these private investors to the environmental and social consequences of the Xayaburi Dam is limited (ibid.). This circumstance can cause problems that Laos has to be prepared to manage since the impacts of large-scale hydro energy projects on waterbeds, water-connected ecosystems and the displacement of people are extensive (Chattranond, 2018, p. 54). The Mekong is classified as the second most biodiverse river in the world, with 65 million people living in mostly rural areas, who are dependent on fishery and rice to maintain food security (Alastair, 2015, p. 144). Also, despite hydropower projects portraying an opportunity for stronger regional connections in the LM, it holds great potential for conflicts. Alastair (2015, pp. 145) points out that the dam and the involved bureaucratic institutions have failed to reconcile the competing interests of the states impacted by the dam, and that the consultation process of the MRC should be improved to lower the level of regional disagreement on dams. The portrayed challenges demonstrate “[the allocation of] water–energy […] [as something that] describes competition between different goods: energy production versus environmental and social protection. This materializes as competition between bureaucracies in charge of producing these goods: the environment and energy bureaucracies (Hesengerth, 2018, p. 912).

Conclusion

The allocation of energy as a scarce resource in growing demand has presented Laos with promising opportunities for economic development and regional energy networking. After the GFC, its economic priorities have shifted even more concentratedly to using natural resources as a foundation for economic growth and changing institutions with the same motivation. The process of hydroenergy adaptation resulted in various changes to institutions in Laos. The country became more incorporated into the global and regional markets with increasingly diversified actors. The Xayaburi Dam also changed the manner transboundary water governance was conducted. The field of water governance requires further development and adaptation for more effective challenge-tackling endeavors, visible in the case of transnational disagreements and the clashes of different bureaucracies. The dam also caused changes in the formal structures of the Laotian government by influencing bureaucratic adaptation to cater to the economic priorities of generating FDI attractiveness and regional connectivity. Finally, the increase in hydropower energy and the resulting economic success of the finished projects have led to an increase and intensification in values of water nationalism in Laos, as well as other LM governments, increasing the potential risk for transnational tensions.

Editor: Maria Trumsi

Copy Editor: Ellen Anderson

Chief Editor: Anahita Poursafir

ReferencesAlistair, R. C. (2015). Notification and consultation procedures under the Mekong agreement: Insights from the Xayaburi controversy. Asian Journal of International Law, 5(1), 143-175.

Chattranond, O. (2018). Battery of Asia? The rise of regulatory regionalism and transboundary hydropower development in Laos.

Electricity in Laos | The Observatory of Economic Complexity. (n.d.). The Observatory of Economic Complexity. https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-product/electricity/reporter/lao

Grumbine, R. E., Dore, J., & Xu, J. (2012). Mekong hydropower: drivers of change and governance challenges. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 10(2), 91-98.

Hensengerth, O. (2018). Where is the power? Transnational networks, authority and the dispute over the Xayaburi Dam on the Lower Mekong Mainstream. In Sustainability in the Water Energy Food Nexus (pp. 199-216). Routledge.

IRENA (2023), Socio-economic footprint of the energy transition: Southeast Asia, International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi.

Jumlongnark, W. (2024). Unraveling the Current Economic Downturn in Laos: A Study of Factors and Implications. Journal of ASEAN PLUS+ Studies, 5(1).

Kyophilavong, P. (2012). The Impact of Global Financial Crisis on Lao Economy: GTAP Model Approach. Journal of US-China Public Administration, 9(3), 280-289.

Mamat, R., Sani, M. S. M., & Sudhakar, K. J. S. O. T. T. E. (2019). Renewable energy in Southeast Asia: Policies and recommendations. Science of the total environment, 670, 1095-1102.

Ministry of Energy and Mines, Laos (2012) Data Collection Study (Preliminary Assessment on Energy Sector in Lao People´s Democratic Republic

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2017). OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Lao PDR. OECD Publishing.

Williamson, O. E. (2000). The new institutional economics: taking stock, looking ahead. Journal of economic literature, 38(3), 595-613.