Geng Jianyi - Eternal Pays of Sun No 2 (1993)

Postmodernism defines a movement that arose as

a reaction to the modernism of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It is thus very difficult to be identified and described without taking into consideration that foregoing period. In China,

modernist art stands for national autonomy—it occurred in a period when the nation went through a series of unfortunate events, such as the defeat in the Opium War and the signing of unequal agreements with some Western powers. These were considered by the population to be extremely humiliating, leading, therefore, to a pronounced reaction that was particularly evident in the art world.

China’s economic reopening that followed this period changed many of the values associated with national identity. However, one needs to first consider that on a more general note, World War I, the Influenza Pandemic, the Wall Street Crash, and the Great Depression weakened many of the

moral certainties of the era, particularly the beliefs in rational thought and the beneficial effects of technology. Later, World War II, the Jewish Holocaust, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the Vietnam War caused people to become increasingly

disillusioned about life. This had an enormous impact on art in general. It announced the close of a white, elitist, male-dominated modernist era—and the rise of more inclusive, brutal, real forms of art. All of this fell under the frame of a wider concept: postmodernist art.

It refers to a category of art that started to become present in people’s lives from the 1960s onwards. This new type of aesthetic opposed the previous modernist technique. With few exceptions, representational art became irrelevant, being replaced by different forms of abstract representations packed with

symbolism and emotions. Postmodernism rejects traditional values and moves away from modern beliefs of how art can be expressed, in favour of

more entertaining art forms such as ‘conceptual art’, ‘performance art’, or ‘installation art’.

It focuses on the free expression of emotions, and if we were to compare it to dress codes, it would be the artistic equivalent of the less formal ‘

jeans and T-shirt’ style, as opposed to the traditional ‘suit and necktie’ style or the modern ‘jacket and trousers’ style. Impressive drawing skills are now less important when compared to original and innovative ideas that instantly trigger reactions from the viewer. In other words,

the concept behind the product becomes more important than the product itself.

Despite the bold, direct, and impactful content, artists usually minimise explicit messages in order for the viewer to

contribute to the piece of art by determining its final meaning themselves. The spectator plays a much more important role, becoming a ‘

judge of meaning’ together with the artist.

China’s economic and cultural reopening in the 1970s provided the perfect conditions for a new type of art to develop. The post-Mao period was marked by socialist reforms aimed at technological innovation and integration with the global economy, thus encouraging

awareness of globalized culture. However, the postmodernist Chinese discourse included

both a sense of integration and a sense of difference. Chinese postmodernity should be understood and analysed in its relationship to a

socialist and revolutionary society. For example, Gu Wenda’s ‘

She X He’ represents an expression of breaking free from the confinement of Socialist Realism by deconstructing language and relating it to the postmodernist notion of identity.

The developments in Postmodernist Chinese art can be divided into

four stages: 1976-84, 1985-89, 1990-99, 2000-present. The first stage includes the post-cultural revolution period; the second, mainly the new wave and avant-garde movements; third, a period of repression and protest; and lastly, the evolution of art up to the present day. However, having the Tiananmen Square events as a reference point, the four stages can be merged, resulting in two major phases: pre-1989 and post-1989.

The

liberation of thought that occurred after the Cultural Revolution encouraged artists to explore the Western art world for the first time in 40 years. Thoughts that had been repressed for so long could finally be released in the form of art. Artists were enthusiastic to discover new theories and aesthetic styles to replace the old Chinese art that had been directed by the state apparatus to serve as political propaganda.

The main themes present in pre-1989 art works were mainly rooted in

the experiences of the Cultural Revolution:

irrational, dehumanising Chinese socialism in opposition to rational and humane Western democracy. An example in this sense could be Wu Shan Zhuan’s installation ‘

Red Humor.’ By filling it with handmade signs featuring a number of political, religious, and advertising texts, the artist criticises situations typical of the Cultural Revolution, where people had to face a chaotic collection of information disconnected from the realities of daily life.

The idea of the West used to bear positive symbolic connotations of freedom, human rights, and liberated sexuality, which were idealised and very often unconsciously sought after by a society that had been cut off from the rest of the world for so long. Having the West as source of inspiration, the ‘

85 New Wave’ avant-garde art movement served as a symbol for the birth of contemporary Chinese art. Despite criticism that this kind of art was nothing more than

a copy of the western art style, it represented a significant step forward for Chinese artists in discovering and experimenting with alternative ways of creating art.

Similarly to the West, this period was marked by movements against the authoritarian political culture in favour of personal liberation, identity investigation, and exploration of anxieties. For example, the exaggerated laughing faces in

‘The Second State’ by Geng Jianyi seem to hide either mocking sneers or terrified screams more than represent instances of genuine laughter. Such interpretations could in fact reflect the

awkwardness towards the social reality at that time.

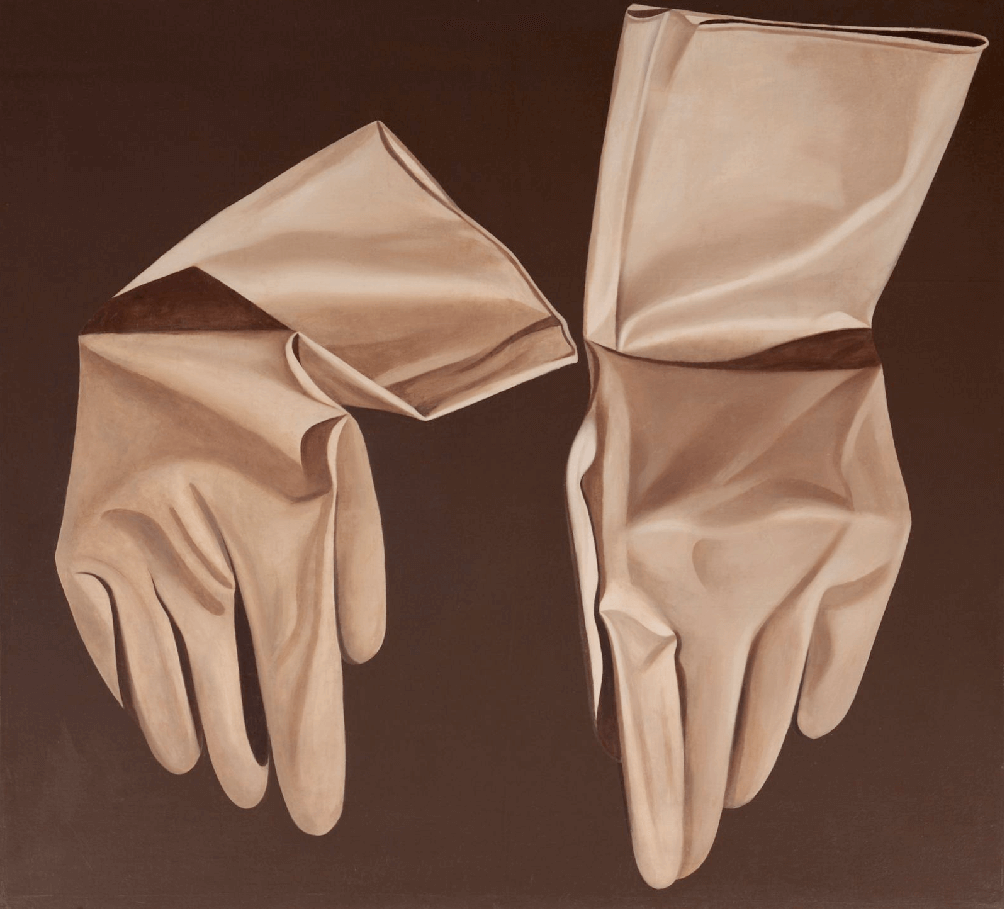

Closely related, the artificial horror and control of modern life is accurately depicted in the

‘X’ series by Zhang Peili. The oversized clinical latex gloves could stand as a metaphor for institutionalised control, for the disconnected and toxic nature of contemporary life, or for a

dehumanised hyper-rationality.

The China/Avant-Garde Exhibition that took place in February 1989 is another significant event in the pre-1989 avant-garde movement. After artist

Xiao Lu opened fire on her installation piece called ‘Dialogue’, the exhibition was temporarily shut down. These shots became known as ‘the first shots of Tiananmen’, as they anticipated the upcoming events in June 1989.

Following the Tiananmen student movement, the Chinese Communist Party started persecuting its political dissidents, who were often part of academic, art, or cultural circles. Works exhibiting Western inclinations were forbidden under a

new law in 1990. However, with the socialist welfare system pulled apart, and the social stratification caused by market liberalisation and foreign capital reaching very high levels, the

pursuit of prosperity on an individual level became the new aspiration of the nation. As a result, exhibition venues in mainland China were wrested back after the Tiananmen movement. The state’s tolerance toward avant-garde art, previously known as ‘unofficial art,’ was grounded in its high degree of market efficiency.

“The West” and “the market” were now synonyms in the eyes of the Chinese population. Consequently, the pre-1989 naive idealisation started converting into less sympathetic sentiments towards the West. Materialism, sexual immorality, and capitalist labor cruelty became the main characteristics associated with the West. One example could be

Hong Hao’s series of ‘Mr. Hong’ and ‘Mr. Gnoh,’ where he satirises the Chinese admiration of Western lifestyles.

The post-1989 postmodernist art switched to a stance where disorientation, frustration, and

exhausted excitement were prevalent. Authenticity and

remaining ‘Chinese’ despite the major process of globalisation were a rising trend in contemporary art as well. For instance, the performance ‘My America’ by Zhang Huan, where a number of Americans throw stale bread at him, is set up in a place that resembles a prison. The intent was to show the

humiliation and imprisonment that comes along with the assimilation of a new culture.

Moreover, the 1990s represented a period of increased involvement of Western agents in the Chinese art world. For Chinese artists, this translated into an opportunity for

self-promotion to the West, through exaggeration, distortion of facts, and

self-exoticizing practices. Hong Lei’s ‘After Song Dynasty Zhao Ji ‘Loquat and Bird’’ is an interesting example in this sense. The dead body of a bird in front of Chinese symbols of prosperity such as peonies and orchids could actually be interpreted as an attack towards

‘selling out' Chinese contemporary art to the West.

Post-1989 Chinese art has also been concerned with representing fragmentation and different forms of everyday life. For example, as an attempt to evoke the incomprehensible and incoherent reality created by the rapid growth of cities—which involves a continuous process of construction and deconstruction—stands Zhan Wang’s ‘

Ruin Cleaning Project ’94’. As his canvas he used a half-demolished building, onto which he started painting doors and windows. However, his work was far from being finished when the building was razed, contributing to a never-ending feeling of helplessness and frustration. Similarly,

Qiu Xiaofei’s 2010 canvas ‘Utopia’ stands as a critique to the rapid growth of cities that displaces the lives of ordinary people forcing them to live in concrete apartment blocks.

All in all, to fully understand the

uniqueness of Chinese Postmodernist art, one needs to consider both its specificity given by internal developments and realities, as well as the condition of postmodernity worldwide. Overall, the combination of these factors led to artists being straightforward in their artistic expressions, and to stress internal turmoil or political repression in their works.

Having as starting point the Cultural Revolution, Chinese Postmodernist Art moved from an acute need to idolise and imitate ‘the West’ to a period where the approach to the Western ideal crumbled, reaching a point where remaining “Chinese” in the face of globalisation turned into a major concern.