Watching Japanese black and white movies from the 50’s might seem like a strange activity for a Friday night in 2021, but the beauty of Yasujirō Ozu’s movies is that they seem just as relatable, relevant and rewarding today as they were seventy years ago upon their first release.

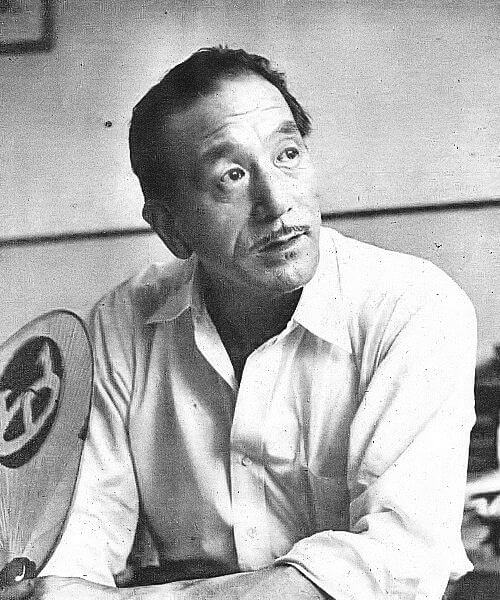

Ozu was a Japanese film director, born around the turn of the last century. His career began with silent films, but eventually he started doing talkies. After the war, he produced his most famous and successful movies, like “Late Spring” (1949), “Floating Weeds” (1959) and “Tokyo Story” (1953). He is one of those people who is quite famous among students and professionals of film studies but virtually unknown to the population at large. In one composite

ranking of critics, academics, directors and distributors made by British film magazine “Sight & Sound” in 2012, “Tokyo Story” was ranked the third greatest movie ever made—quite an impressive result to say the least.

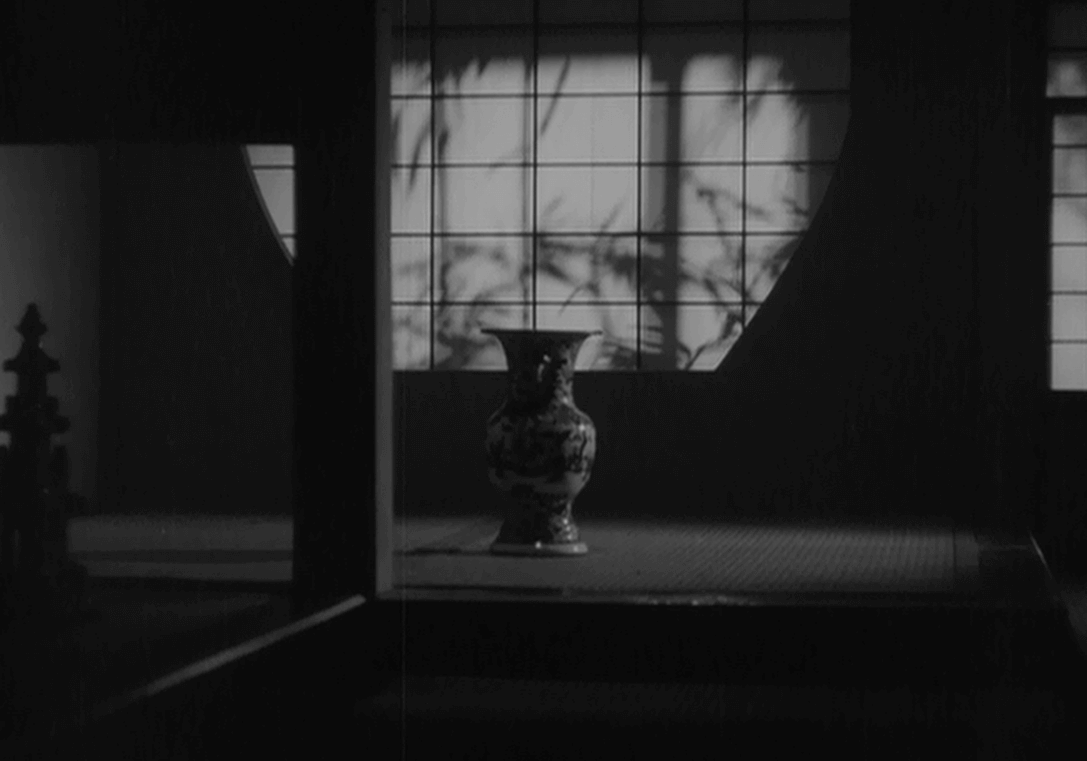

Why is this? What makes “Tokyo Story” and Ozu’s other movies so unique and appreciated? Well, there are lots of things that are special about him. For one, he is the polar opposite of an action director. If we take “Tokyo Story” as an example, there is very little in terms of dramatic scenes—in fact, the drama that exists is often purposefully left off-screen. Instead, we get a number of filler shots between scenes, like a fishing boat tugging out to sea, an empty hallway or a shop sign. He does not want to lead the viewer by the hand by showing exactly what happens at a high pace, but relies instead on small nods and hints of emotions.