View on Gamcheon Culture Village in Busan

Source: Olivia Culot

The city of Busan was a refuge during the Korean War, a haven to half a million refugees in 1951. Indeed, the “Busan Perimeter” was the only southern territory North Korea never conquered, forcing refugees and UN troops to fall back on this small area as a last line of defense.

It is in this context in which Gamcheon was established. Before the war, Gamcheon was sparsely developed, and therefore was spacious enough to accommodate the massive influx of refugees. At that time, around 20 houses only stood at the bottom of the hill. In a few days only, hundreds of houses were built, transforming this quasi-wasteland into a

real shantytown. Refugees used wood, found planks and iron pieces to build shelters, and used stones to prevent them from being blown away by the wind. After the war,

around 800 Taegeukdo devotees were sent to Gamcheon by the city, temporarily changing its name to Taegeukdo Village. Taegeukdo is a religion funded by Cho Cholje worshiping the yin and yang (Taegeuk), the “great polarity” as the foundation of the universe. The Taegeuk is a national symbol and can be seen on the Korean flag. Cho managed to convert around 90% of the refugees with candies, toothbrushes and rice. Together, they worked on rebuilding up the town. Bricks replaced wood, and even two story houses were built in the late 1980s. However, Gamcheon developed at a slower rate and fell further behind other neighborhoods: high poverty and unemployment rates made its inhabitants move out of the town, leaving empty houses as Gamcheon became once again a real slum. The population dropped

from 30 000 to 8 000 people, mostly the elderly were left behind.

South Korea has sought to solve population concentration issues due to urbanization by developing new cities since the 1980s. At first, development projects focused on economic growth, generating negative side effects (economic inequality between regions, environmental degradation). This is where Gamcheon’s story becomes quite unique, as it embodied a different approach. 2009 marks the start of different initiatives, mostly art-related, to transform the village with culture and creativity as the keys to Gamcheon’s development. The strategy was to bet on the already-existing singular characteristics of the town, small houses and streets stacked on a hillside. These projects included participation and consultation from residents, local administrators, and external artists. Therefore, the revitalisation was not just imposed by external authorities but is also based on the

ideas and thoughts of the local population. Indeed, working groups with residents brainstormed on how to improve the town and community. Smaller initiatives emerged: cleaning the streets, creating new businesses, renovating houses (especially those occupied by elderly lower income residents), as well as more important projects such as building a sewage system and running water facilities (virtually nonexistent at the time). Finally, residents were offered classes on skills including management of business and sales techniques.

The key initiative was the art promotion project conducted by the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism. The “Dreaming of Machu Picchu in Busan'' project combined not only the aforementioned initiatives, but also the funding of ten art projects, and was the first step toward transforming Gamcheon into a place of culture and art. The “Miro Miro” (“maze” in Korean) project added 12 more pieces to the previous ten, such as sculptures and murals which were placed across the city, as well as “alley painting”: arrows on houses to indicate the way for visitors. Moreover, the “Growing through Art” initiative trained residents to offer guided tours of the city, workshops for children, and pottery and clothes dyeing among other activities. The “Empty House Residency Preservation Project'' turned abandoned habitations into various workshops, occupied by artists since 2015, their artworks displayed in special galleries for free. One of them, the Saekjeuksigong, is lent to artists for a year, and operates as a workshop and gallery. Another noticeable project is the restoration of an abandoned school into a cultural and welfare centre. Finally, the Busan Metropolitan Government gives a subsidy of around

KRW 500 million every year to the town.

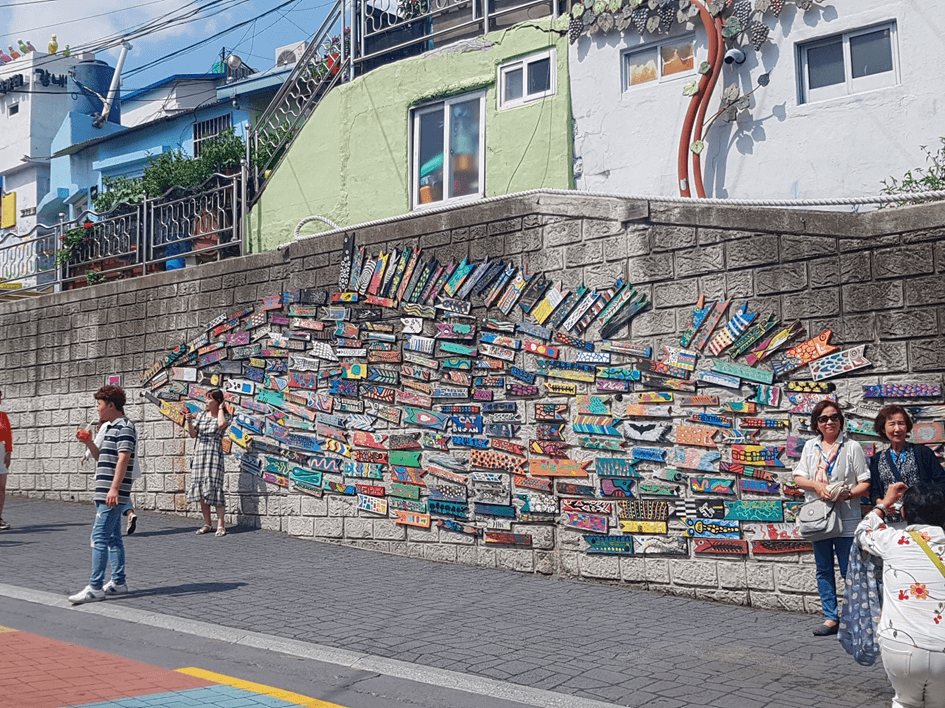

Wooden fish wall art in Gamcheon, near the main entrance

Source: Olivia Culot

Overall, colourful painting on houses combined with narrow streets layered on the foot of the Cheonmasan Mountain gave a quaint atmosphere propitious for tourism. Other curiosities include the Tower of Doknak at the entrance and the “Star Stairs Houses”, designed by different architects to embellish the village. Each of those places has unique features, such as special windows creating an unusual vibe. The “Book Café”, for example, is a building shaped like a coffee mug. There are currently around 40 art displays in Gamcheon. Many are fit perfectly in the era of Instagram and social media, and people queue to take pictures sitting next to the Little Prince statue seemingly tailor-made for this purpose. The village also offers small museums, restaurants, art workshops and even hanbok (Korean traditional clothing) rentals.

The Young Prince and Desert Fox statue

Source: Olivia Culot

These programs provided jobs and income for the population, and the revenues were put to good use: food distribution and the organization of public events. 25 000 people now live in Gamcheon and 120 artists have contributed to the village to date. To give an idea to the degree of the local population’s involvement, they opened

11 new businesses, 17 cooperatives and 2 NGOs in 2016 alone. It has become one of Busan’s but also South Korea’s more peculiar attractions, winning several prizes such as the

cultural excellence award from the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism.

If it seems an unmitigated success story, look closer. The opinion of the local population is more divided. While they were skeptical of the project at first, many accepted and appreciated it as it gave a new charming look to their hometown. But as time passed, more than a half of residents have not been satisfied with the changes.

66% said that they believe it did not increase employment as expected, leading to the lowest-income residents leaving the village (not everyone can become an artist, chef or a tourist guide). Moreover, mass tourism disturbs local life, because no obvious distinction is made between tourist spots and residential areas. Obviously, the pandemic drastically reduced the amount of visitors, postponing this issue. However, a

participatory study suggested some solutions, including creating items (souvenirs) and food which would be specific to Gamcheon, retaining bus revenue for the village, and being more explicit about town residents to generate more consideration from the tourists.

On the other hand, the cultural impact is undeniable because the Gamcheon Culture Village is, well, a place of culture. The

OECD considers this regeneration an exemplary success, especially in the realms of collaboration between authorities and local populations, as well as in urban development. It is also an example of utilizing specific traits of a place to resurrect it instead of restarting the developing process from scratch. Keeping historical features but adding special twists to it, and betting on culture, art and tourist appeal to make it a unique, pretty, and successful developmental project.