Empress Suiko, the first Empress of Japan who ruled from 592 - 628

The status of women in Japan has undergone several dramatic shifts over the course of the nation’s history. Women from the Heian Period (794 -1185) enjoyed near complete equality, having the rights to own assets, and wielding a great deal of influence over legal proceedings. The country was even ruled by at least 8 Empresses, most recently in the 18th century.

The major degradation of women’s rights in Japan came towards the end of the Edo period (1603-1867), continuing into the Meiji era (1868 – 1912). The importation of Western conservative family values and gender roles, along with the introduction of the Ie system in 1898, stripped women of essentially all rights and relegated them to subservient housekeepers. Although women’s rights in Japan would rebound after the enactment of the modern Japanese constitution in 1947, Japan still significantly lags behind the rest of the developed world regarding gender equality, despite women playing an ever more valuable role in contemporary Japanese society. After all, it was the schoolgirls of the 90s who pioneered SMS and introduced emojis to the world.

“Idols” have become the most prominent, and arguably most controversial representation of women in Japanese media. Idols are tricky to describe; In essence, they are young female entertainers, typically aged from preteen to mid-twenties, primarily chosen for their image and marketability. Despite occupying a space that lies somewhere between a singer, performer, influencer, sex symbol, and role model, an idol’s actual “talent” is their marketability and likeability. Often the more unconventional, awkward, and cutesy they are, the better. It is largely for this reason that idols’ fans are almost entirely composed of men at least double their age.

Hibari Misora, Japan's first idol

This uniquely Japanese phenomenon can actually trace its origins to a 1964 French-Italian film titled “Cherchez l'idole”. During these formative years young female musicians like Hibari Misora and Matsuko Ashita won over hearts and sang away the post-war blues, heralding a new and optimistic era for Japan. TV singing contests and massive exposure through ads and magazines lodged idols firmly into the Japanese public consciousness throughout the 70s, and by the early 80s, idol mania had reached its peak.

Talent agencies were pumping out more idols than the public could even keep up with, and idol music packed the Japanese charts. It seemed like nothing could stop the idol hype, not even the retirement of Momoe Yamaguchi, one of the most successful musicians in Japanese music history, at the pinnacle of her career in 1980. But the shimmering highs of idol obsession would soon come crashing down to earth with a sobering and resounding thud.

On April 8th, 1986, the idol Yukiko Okada leapt to her death in broad daylight, from the top floor of the Sun Music building in downtown Tokyo. As the 18-year-old’s body was swarmed by droves of TV reporters and sobbing fans, the sobering reality of the demanding and intensely restrictive idol life came into focus. Okada’s death caused an overnight shift in perception, and Idols fell sharply out of fashion as the public grew weary of their oversaturation and began shifting its focus towards more traditionally talented female artists.

Yukiko Okada performing in 1984

Source: wikimedia commons

The release of Satoshi Kon’s seminal anime film “Perfect Blue” in 1995 dealt another blow to the industry, publicizing the overt sexualisation, abuse, and intense psychological pressure idols are subjected to. As the 90s rolled on, it seemed that idols would largely fade into the past, relics of the mythical days before Japan’s economic bubble imploded. But as the new millennium approached, idols were primed to make an unprecedented comeback.

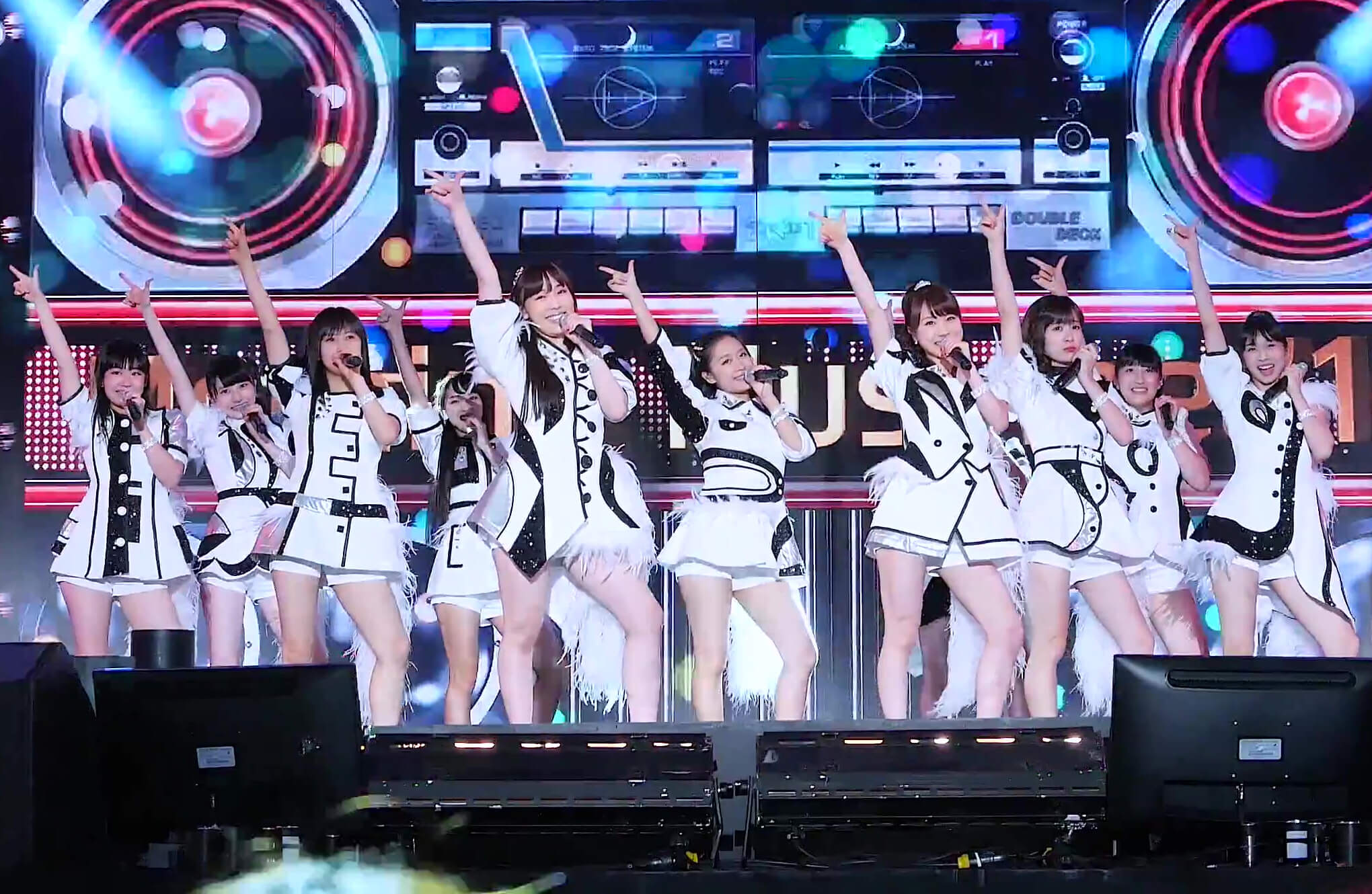

The group Morning Musume’s relatively unassuming debut in 1997 is credited with kickstarting an idol renaissance. Idols were no longer merely the pastel-clad solo singers of yesteryear. They had evolved into enormous, multifaceted and highly marketable groups.

Morning Musume performing in Korea in 2016

Fan interaction became central to the idol revival, with the internet enabling fans and idols to connect like never before. The explosive debut of the now infamous AKB-48 in 2005 took this interaction to the next level, giving fans the opportunity to directly influence the group, through intensely competitive elections and televised singing contests. AKB’s rabid popularity kicked off yet another idol gold rush, one which continues to the present day.

There are currently over 10,000 idols and around 3,000 idol groups throughout Japan, all competing for their moment in the spotlight. Idols have become a mainstay of the Japanese entertainment industry, a significant tour de force which rakes in nearly 9 billion SEK a year.

Some of the members of AKB-48 in 2010

But danger loomed in the shadows of these gleaming ascensions to stardom. The intense push behind fan interaction, through social media and meet-and-greet handshake events has encouraged a progressively more unhealthy relationship between idols and their increasingly radicalised fans. Idols are often portrayed as being cutesy and naive through their general image and even the lyrics in their music, however it’s this focus on youth and vulnerability which places them at the centre of the lives of so many disenfranchised people. The dangerous fixation on superficial attributes and consumption has only encouraged unhealthy levels of complete obsession amongst the most dedicated fans, who often see their favourite idols as if they own them.

The industry has desperately sought to maintain this level of obsession and hype at all costs, going as far as to impose tight restrictions on idol’s lives, movements, and even their diets. Idol’s public images are meticulously pruned to suit the expectations of their fans, with often very serious repercussions for anything which threatens to ruin this facade. Romantic relationships often carry the biggest penalty, with idols often being contractually obliged not to engage in them, and even the most frivolous encounters leading to teary-eyed apologies to fans or idols forcefully resigning from their groups in disgrace. Yukiko Okada’s suicide has often been attributed to the breaking up of a relationship between her and a co-star. By giving up their lives and liberties, Idols essentially only exist to entertain. As the lines between reality and fantasy have become blurred, parasocial relationships between obsessive fans and idols with whom they believe they have a legitimate and meaningful connection with have become rampant within the fandom, often with very real-world consequences.

Perfect Blue’s stark and violent portrayal of the idol industry stunned both domestic and international audiences on its debut nearly 30 years ago. However, it’s hard to believe this depiction would end up being more relevant today than ever before. Assaults on idols have become shockingly common in recent years, with some being attacked, stalked, and even brutally stabbed by obsessive fans. Even groups like AKB-48 weren’t big enough to escape the madness; Two members were attacked with a saw at a fan event in 2014. All the while, police forces, government officials and fans have shrugged their shoulders, disregarding the attacks as mere occupational hazards and further sweeping the plight of the young women in Japan’s entertainment industry under the carpet.

With idols becoming as big a part of the Japanese entertainment scene as they were in their heyday, and with idol-like expectations being imposed on women in other areas of Japanese media, it seems increasingly unlikely that anything will change in the near future.